#FactCheck - Viral Post of Gautam Adani’s Public Arrest Found to Be AI-Generated

Executive Summary:

A viral post on X (formerly twitter) shared with misleading captions about Gautam Adani being arrested in public for fraud, bribery and corruption. The charges accuse him, his nephew Sagar Adani and 6 others of his group allegedly defrauding American investors and orchestrating a bribery scheme to secure a multi-billion-dollar solar energy project awarded by the Indian government. Always verify claims before sharing posts/photos as this came out to be AI-generated.

Claim:

An image circulating of public arrest after a US court accused Gautam Adani and executives of bribery.

Fact Check:

There are multiple anomalies as we can see in the picture attached below, (highlighted in red circle) the police officer grabbing Adani’s arm has six fingers. Adani’s other hand is completely absent. The left eye of an officer (marked in blue) is inconsistent with the right. The faces of officers (marked in yellow and green circles) appear distorted, and another officer (shown in pink circle) appears to have a fully covered face. With all this evidence the picture is too distorted for an image to be clicked by a camera.

A thorough examination utilizing AI detection software concluded that the image was synthetically produced.

Conclusion:

A viral image circulating of the public arrest of Gautam Adani after a US court accused of bribery. After analysing the image, it is proved to be an AI-Generated image and there is no authentic information in any news articles. Such misinformation spreads fast and can confuse and harm public perception. Always verify the image by checking for visual inconsistency and using trusted sources to confirm authenticity.

- Claim: Gautam Adani arrested in public by law enforcement agencies

- Claimed On: Instagram and X (Formerly Known As Twitter)

- Fact Check: False and Misleading

Related Blogs

Executive Summary

A shocking video claiming to show snakes raining down from the sky is going viral on social media. The clip shows what appear to be cobras and pythons falling in large numbers instead of rain, while people are seen running in panic through a marketplace. The video is being shared with the claim that it is the result of “tampering with nature” and that sudden snake rainfall occurred in an unidentified country. (Links and archived versions provided)

CyberPeace researched the viral claim and found it to be false. The video does not depict a real incident. Instead, it has been generated using artificial intelligence (AI).

Fact Check

To verify the authenticity of the video, we extracted keyframes and conducted a reverse image search using Google Lens. However, we did not find any credible media report linked to the viral footage. We also searched relevant keywords on Google but found no reliable national or international news coverage supporting the claim. If snakes had genuinely rained from the sky in any country, the incident would have received widespread media attention globally. A frame-by-frame analysis of the video revealed multiple inconsistencies and visual anomalies:

In the first two seconds, a massive snake appears to fall onto electric wires, yet its body passes unrealistically through the wires — something that is physically impossible. The snakes falling from the sky and crawling on the ground move in an unnatural manner. Instead of falling under gravity, they appear to float mid-air. Around the 9–10 second mark, a person lying on the ground has a visibly distorted hand structure, a common artifact seen in AI-generated videos.

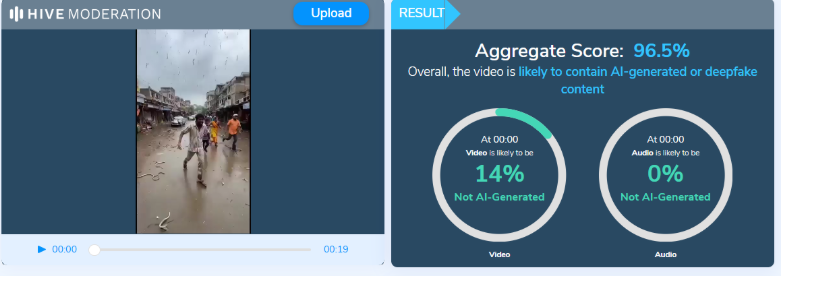

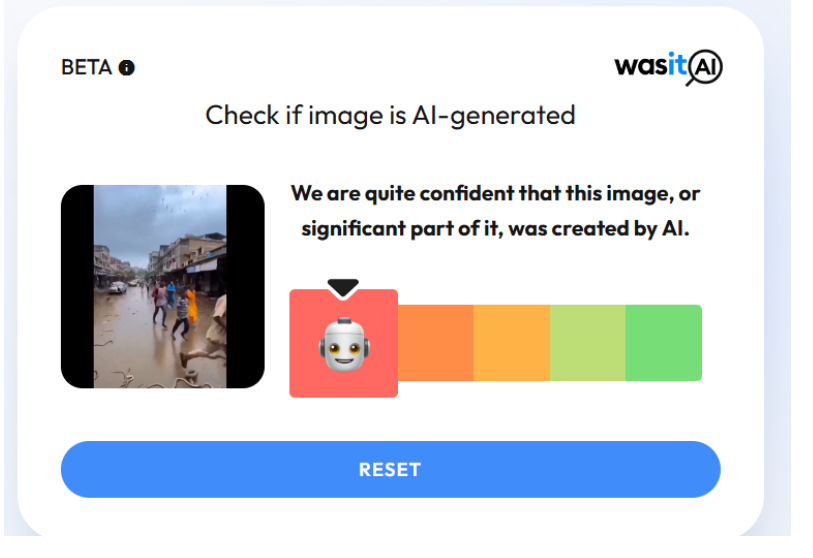

Such irregularities are typical indicators of AI-generated content. The viral video was further analyzed using the AI detection tool Hive Moderation, which indicated a 96.5% probability that the video was AI-generated.

Additionally, image detection tool WasitAI also classified the visuals in the viral clip as highly likely to be AI-generated.

Conclusion

CyberPeace ’s research confirms that the viral video claiming to show snakes raining from the sky is not authentic. The footage has been created using artificial intelligence and does not depict a real event.

A report by MarketsandMarkets in 2024 showed that the global AI market size is estimated to grow from USD 214.6 billion in 2024 to USD 1,339.1 billion in 2030, at a CAGR of 35.7%. AI has become an enabler of productivity and innovation. A Forbes Advisor survey conducted in 2023 reported that 56% of businesses use AI to optimise their operations and drive efficiency. Further, 51% use AI for cybersecurity and fraud management, 47% employ AI-powered digital assistants to enhance productivity and 46% use AI to manage customer relationships.

AI has revolutionised business functions. According to a Forbes survey, 40% of businesses rely on AI for inventory management, 35% harness AI for content production and optimisation and 33% deploy AI-driven product recommendation systems for enhanced customer engagement. This blog addresses the opportunities and challenges posed by integrating AI into operational efficiency.

Artificial Intelligence and its resultant Operational Efficiency

AI has exemplary optimisation or efficiency capabilities and is widely used to do repetitive tasks. These tasks include payroll processing, data entry, inventory management, patient registration, invoicing, claims processing, and others. AI use has been incorporated into such tasks as it can uncover complex patterns using NLP, machine learning, and deep learning beyond human capabilities. It has also shown promise in improving the decision-making process for businesses in time-critical, high-pressure situations.

AI-driven efficiency is visible in industries such as the manufacturing industry for predictive maintenance, in the healthcare industry for streamlining diagnostics and in logistics for route optimisation. Some of the most common real-world examples of AI increasing operational efficiency are self-driving cars (Tesla), facial recognition (Apple Face ID), language translation (Google Translate), and medical diagnosis (IBM Watson Health)

Harnessing AI has advantages as it helps optimise the supply chain, extend product life cycles, and ultimately conserve resources and cut operational costs.

Policy Implications for AI Deployment

Some of the policy implications for development for AI deployment are as follows:

- Develop clear and adaptable regulatory frameworks for the ongoing and future developments in AI. The frameworks need to ensure that innovation is not hindered while managing the potential risks.

- As AI systems rely on high-quality data that is accessible and interoperable to function effectively and without proper data governance, these systems may produce results that are biased, inaccurate and unreliable. Therefore, it is necessary to ensure data privacy as it is essential to maintain trust and prevent harm to individuals and organisations.

- Policy developers need to focus on creating policies that upskill the workforce which complements AI development and therefore job displacement.

- To ensure cross-border applicability and efficiency of standardising AI policies, the policy-makers need to ensure that international cooperation is achieved when developing the policies.

Addressing Challenges and Risks

Some of the main challenges that emerge with the development of AI are algorithmic bias, cybersecurity threats and the dependence on exclusive AI solutions or where the company retains exclusive control over the source codes. Some policy approaches that can be taken to mitigate these challenges are:

- Having a robust accountability mechanism.

- Establishing identity and access management policies that have technical controls like authentication and authorisation mechanisms.

- Ensure that the learning data that AI systems use follows ethical considerations such as data privacy, fairness in decision-making, transparency, and the interpretability of AI models.

Conclusion

AI can contribute and provide opportunities to drive operational efficiency in businesses. It can be an optimiser for productivity and costs and foster innovation for different industries. But this power of AI comes with its own considerations and therefore, it must be balanced with proactive policies that address the challenges that emerge such as the need for data governance, algorithmic bias and risks associated with cybersecurity. A solution to overcome these challenges is establishing an adaptable regulatory framework, fostering workforce upskilling and promoting international collaborations. As businesses integrate AI into core functions, it becomes necessary to leverage its potential while safeguarding fairness, transparency, and trust. AI is not just an efficiency tool, it has become a stimulant for organisations operating in a rapidly evolving digital world.

References

- https://indianexpress.com/article/technology/artificial-intelligence/ai-indian-businesses-long-term-gain-operational-efficiency-9717072/

- https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/artificial-intelligence-market-74851580.html

- https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbestechcouncil/2024/08/06/smart-automation-ais-impact-on-operational-efficiency/

- https://www.processexcellencenetwork.com/ai/articles/ai-operational-excellence

- https://www.leewayhertz.com/ai-for-operational-efficiency/

- https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbestechcouncil/2024/11/04/bringing-ai-to-the-enterprise-challenges-and-considerations/

Over The Top (OTT)

OTT messaging platforms have taken the world by storm; everyone across the globe is working on OTT platforms, and they have changed the dynamics of accessibility and information speed forever. Whatsapp is one of the leading OTT messaging platforms under the tech giant Meta as of 2013. All tasks, whether personal or professional, can be performed over Whatsapp, and as of today, Whatsapp has 2.44 billion users worldwide, with 487.5 Million users in India alone[1]. With such a vast user base, it is pertinent to have proper safety and security measures and mechanisms on these platforms and active reporting options for the users. The growth of OTT platforms has been exponential in the previous decade. As internet penetration increased during the Covid-19 pandemic, the following factors contributed towards the growth of OTT platforms –

- Urbanisation and Westernisation

- Access to Digital Services

- Media Democratization

- Convenience

- Increased Internet Penetration

These factors have been influential in providing exceptional content and services to the consumers, and extensive internet connectivity has allowed people from the remotest part of the country to use OTT messaging platforms. But it is pertinent to maintain user safety and security by the platforms and abide by the policies and regulations to maintain accountability and transparency.

New Safety Features

Keeping in mind the safety requirements and threats coming with emerging technologies, Whatsapp has been crucial in taking out new technology and policy-based security measures. A number of new security features have been added to WhatsApp to make it more difficult to take control of other people’s accounts. The app’s privacy and security-focused features go beyond its assertion that online chats and discussions should be as private and secure as in-person interactions. Numerous technological advancements pertaining to that goal have focussed on message security, such as adding end-to-end encryption to conversations. The new features allegedly increase user security on the app.

WhatsApp announced that three new security features are now available to all users on Android and iOS devices. The new security features are called Account Protect, Device Verification, and Automatic Security Codes

- For instance, a new programme named “Account Protect” will start when users migrate an account from an old device to a new one. If users receive an unexpected alert, it may be a sign that someone is trying to access their account without their knowledge. Users may see an alert on their previous handset asking them to confirm that they are truly transitioning away from it.

- To make sure that users cannot install malware to access other people’s messages, another function called “Device Verification” operates in the background. Without the user’s knowledge, this feature authenticates devices in the background. In particular, WhatsApp claims it is concerned about unlicensed WhatsApp applications that contain spyware made explicitly for this use. Users do not need to take any action due to the company’s new checks that help authenticate user accounts to prevent this.

- The final feature is dubbed “automatic security codes,” It builds on an already-existing service that lets users verify that they are speaking with the person they believe they are. This is still done manually, but by default, an automated version will be carried out with the addition of a tool to determine whether the connection is secure.

While users can now view the code by visiting a user’s profile, the social media platform will start to develop a concept called “Key Transparency” to make it easier for its users to verify the validity of the code. Update to the most recent build if you use WhatsApp on Android because these features have already been released. If you use iOS, the security features have not yet been released, although an update is anticipated soon.

Conclusion

Digital safety is a crucial matter for netizens across the world; platforms like Whatsapp, which enjoy a massive user base, should lead the way in terms of OTT platforms’ cyber security by inculcating the use of emerging technologies, user reporting, and transparency in the principles and also encourage other platforms to replicate their security mechanisms to keep bad actors at bay. Account Protect, Device Verification, and Automatic Security Codes will go a long way in protecting the user’s interests while simultaneously maintaining convenience, thus showing us that the future with such platforms is bright and secure.

[1] https://verloop.io/blog/whatsapp-statistics-2023/#:~:text=1.,over%202.44%20billion%20users%20worldwide.